How UP-created models improve watershed monitoring in an age of failed flood control programs

One thing made obvious by the recent flood control-related controversy was how all that wasted money could have protected people from water-related perils. While the Philippines is no doubt blessed with bountiful water resources, poor management can turn these assets into agents of disaster.

It does not take much to tip the scales. For instance, simply having too much water too fast can instantly devastate communities or cripple a city. Likewise, when waterborne waste goes unmonitored, these can have literally downstream effects that threaten both lives and livelihoods.

Dr. Mayzonee Ligaray was doing her graduate studies in Ulsan, South Korea, when she witnessed firsthand how that country used data to manage their water resources the right way. “In Korea,” she said, “anyone can access all this environmental data.” And this openness has inspired the flowering of AI-based technologies that constantly monitor Korea’s water resources accurately and remotely.

When she came home after finishing her PhD and postdoctoral studies, Ligaray’s mission was clear: to find a way to somehow harness the powers of data, AI, and remote sensing to serve a country that was simultaneously larger, tropical, and completely archipelagic. Thus, together with members of her Environmental Hydrology Laboratory at the Institute of Environmental Science and Meteorology, University of the Philippines Diliman, she launched the Artificial Intelligence-based Sustainable Water Resources Management in the Philippines or AI-SWaMP project in December 2024.

The ultimate goal of AI-SWaMP is to use artificial intelligence to create an optimized model, a kind of digital twin, of our country’s wetlands and watersheds. Using data collected from various sources, Ligaray’s team teaches machines to listen to water, and to learn how it moves, where it comes from, and how it might behave.

It is a model that grows smarter the more data you feed it. The AI-SWaMP team hopes that this fact will allow the government to make better decisions to save our watersheds. And, hopefully, save us, too.

Beneficial use

One big challenge of adapting models and algorithms developed in other countries for local use is how much data it will take. And, for at least our watersheds, that is data we currently do not have. At least not in any consolidated fashion.

The team realized it needed help. That is why recently, AI-SWaMP partnered with both the Laguna Lake Development Authority and the Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewage System. The historical data that these parties offer help paint a clearer picture of how our watersheds have behaved over time. With these contributions, the team now has a broader view of how large watersheds like the Pampanga River Basin and the Pasig-Marikina Laguna Lake Catchment have flowed and changed across decades.

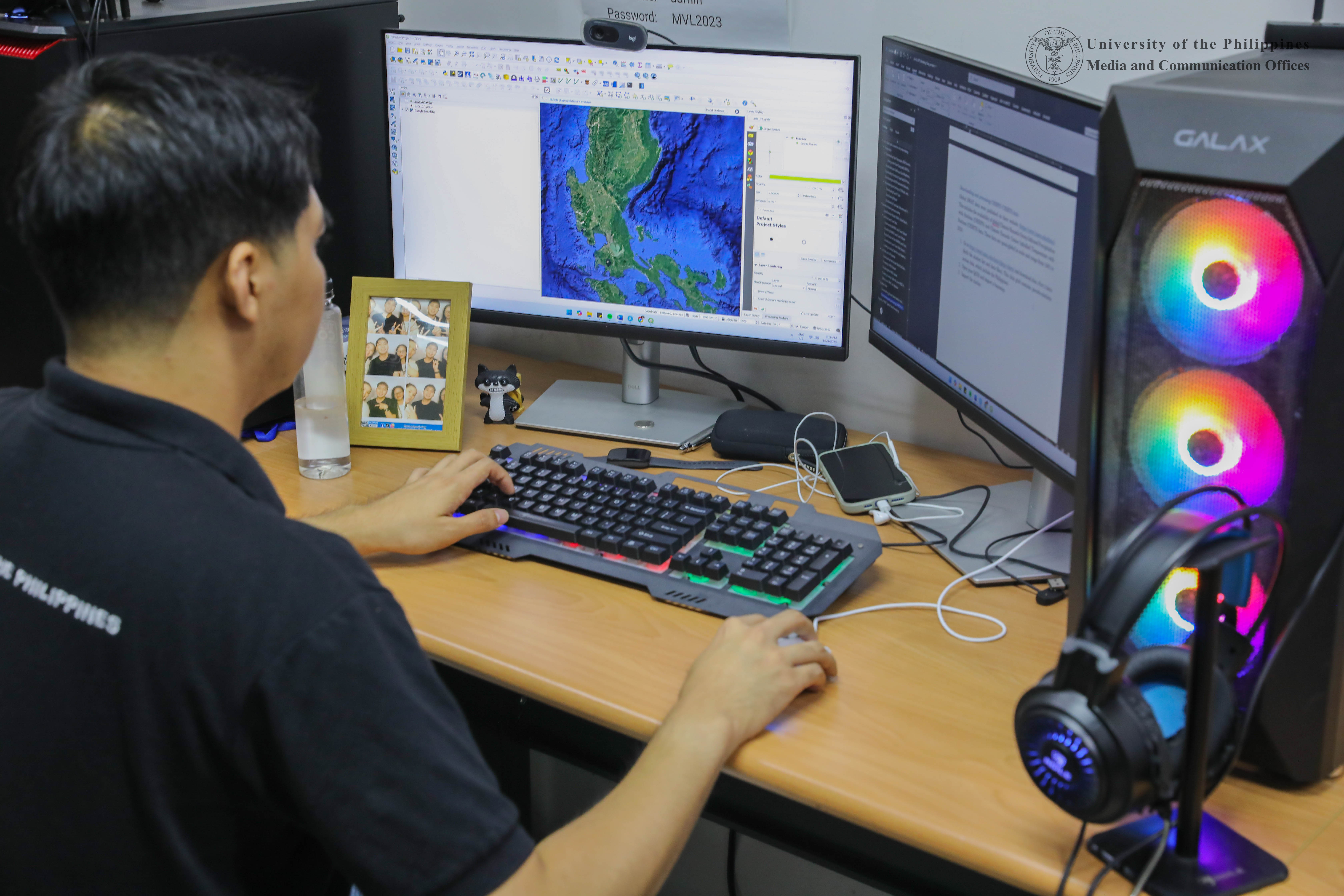

To match this, the team has been collecting satellite data about these watersheds, specifically optical data like Red, Green, Blue or RGB from the Copernicus Programme’s Sentinel-2 Satellite. Then, with the help of deep learning models, the team can begin associating select parameters with real-world watershed states via partner data and information collected on site by the AI-SWaMP team.

We can illustrate the fruits of this process through something critical to our daily lives — water quality. Different water bodies are classified based on their “beneficial use,” each having their respective quality standards and benchmarks. In other words, water that is used for different socially or economically important purposes are treated differently. “So, if one is classified for water supply use, they have very specific standards of, for example, cleanliness. Of course they still treat the water, but there are clear economical conditions for types of water bodies that can be used in this specific way.”

The AI-SWaMP team wants to find relationships between these specific standards or parameters and the presence of possible pollutants, and then trace how these might move across a given watershed system to their real-world endpoints.

Which parameters are most important? Ligaray highlighted some major ones. “For example, if you have a spike in nitrates, that suggests agricultural activity. Because fertilizers have nitrogen compounds.”

A spike in the number of phosphates, on the other hand, without the presence of nearby farmlands, suggests another problem, which is that nearby kitchen sinks and showers either have no septic tanks or are not connected to them. “That’s because there are a lot of phosphates in the things we use for cleaning and hygiene. Like detergents, soaps, and shampoos.” Other things they aim to detect are ammonia from human or animal waste, and particulates in water from soil or dust particles that typically require dredging.

Knowing all this, it becomes clear why AI-SWaMP’s models must replicate the actual movements of water. “The water itself is carrying all these pollutants,” Ligaray said. “So if we know how it behaves and circulates, we can know where the pollutants might come from, and where they may eventually end up.”

Dr. Mayzonee Ligaray presents AI-SWaMP to the Pasig City government and has her photo taken with Mayor Vico Sotto and Councilor Kiko Rustia. Photos from the E-Hydro Lab.

Without plan or purpose

The end goal, of course, is for the group’s partners, such as environmental personnel in the LLDA and the MWSS, to eventually be able to use these models. That way, any interventions they or others might implement will be guided by the best information available.

“By then you can target a problem when designing an intervention or strategy,” Ligaray said. “You can place a specific sewage treatment plant here or you can create a natural buffer that traps waste. Now we have so many interventions but we don’t know yet which are appropriate for which watersheds.”

These are not the only decisions that stand to benefit from AI-SWaMP’s models. One of the team’s collaborators is the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical, and Astronomical Services Administration. Accordingly, Ligaray’s team is helping to improve the agency’s flood models by using satellite images to better estimate flood water depth. “That way, you don’t need to go to the actual flooded area to take measurements or rely on equipment that might break down,” she noted.

Due to their lofty goals, the AI-SWaMP team also continuously gains and continues to pursue partnerships. Even within the IESM, other experts have been rallying under their banner, each making contributions to make the models more powerful and adaptable. Recently, the team’s models have been enriched by the expertise of three more faculty members: Dr. Bernard Alan Racoma (remote sensing), Dr. Mylene Cayetano (environmental chemistry), and Dr. Jane Delfino (climate modeling).

What end does Ligaray have in mind for this considerable combo of talents? For one, she hopes her team can steer the country away from a type of development and urbanization with no clear plan or purpose, but which, unfortunately, has been far too prevalent. A major example of this involves the very same flood control projects that sparked nationwide outrage this 2025.

“There are flood control infrastructures that hinder natural processes,” she said. “We were studying one watershed where a flood control infrastructure was built. But apparently it redirected the water in such a way that the watershed’s groundwater could not be replenished. That, combined with over-extraction, meant the water ran out and the ground eventually caved in.”

“That’s the risk if you do not know your watershed,” Ligaray warned. “Other flood control projects even make flooding worse. So, we want our models to help people understand what really happens in the environment. Hopefully then, we can implement infrastructure projects that actually make things better, and not worse.”

Get in touch with AI-SWaMP and the IESM’s Environmental Hydrology Laboratory here.

Cover photo by Mar Lopez, UPS-MCO.

- Artificial Intelligence-based Sustainable Water Resources Management in the Philippines (AI-SWaMP) is a three-year project, led by Mayzonee V. Ligaray Ph.D. from the University of the Philippines Diliman – Institute of Environmental Science and Meteorology (UPD-IESM) in collaboration with Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) and Pusan National University. AI-SWaMP is funded by the DOST-Grants-in-Aid Program with Philippine Council for Industry, Energy and Emerging Technology Research and Development (PCIEERD) as the monitoring agency and University of the Philippines Diliman as the implementing agency. The project aims to apply remote sensing techniques, artificial intelligence, and environmental models for a sustainable water resource management of selected Philippine river basins.